Top 3 Myths Of Improving Thoracic Spine Mobility & Health

Jun 14, 2022

Are you looking to improve thoracic mobility?

Have you been banging your head against the wall with thoracic mobility stretches with little return on your investment?

The problem is, there is a lot of short-sighted, overly-reductionist information on the internet about thoracic mobility.

Of all types of mobility, thoracic mobility seems to be the one that falls victim to the idea of “forcing” the body into more mobility via stretches and positions that take the body to an end-range.

My goal with this article is to:

- Debunk myths surrounding thoracic mobility

- Explain the mechanics of thoracic mobility

- Show examples of exercises that will lead to long-term changes in thoracic extension, flexion, and rotation

If you would rather watch than read, see below:

Common Myth #1: Pushing yourself into a range of motion will help you own it

How many times have you seen stretches/positions like this before sold as “thoracic mobility” drills?

It makes sense on the surface that if you can move into a position and stay there, then you can adapt to that range of motion over time.

Does this really work? I’m not opposed to it, but let’s break down why so many people continually have to do these stretches daily just for a few minutes of relief or improved range of motion.

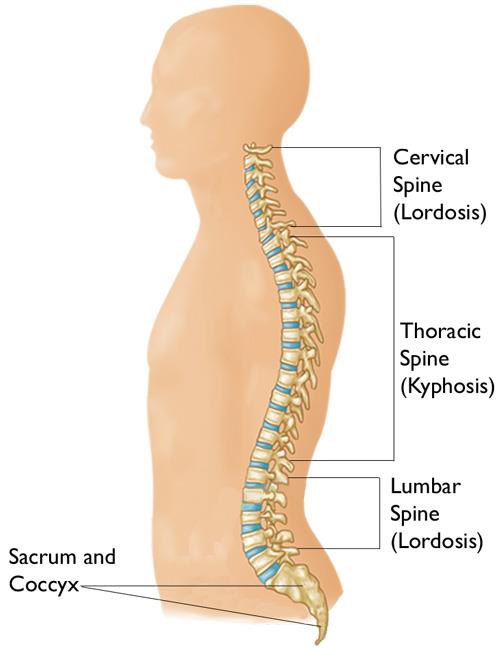

The Thoracic vertebrae make up what most people think of as the “mid” and “upper” back:

Do you notice how a normal human spine curve has a degree of flexion, or rounding, in the thoracic spine? This is what is considered a “neutral” position.

“Neutral” is an important concept because it is the position from which we have the most ability to move in and out of joint actions. If we start from neutral, we can move into flexion, extension, and/or rotation.

However, this is where we can have problems. Do you think you will be able to move into extension if your thoracic spine is already extended?

Can you move into rotation if your thoracic vertebrae are already rotated in a certain direction?

The concept is: We can’t go somewhere we’re trying to go if we’re already there. An extended back will show limitations in extension.

So maybe, shoving ourselves into more extension isn’t solving the problem because we are already starting there.

The mechanics of the thoracic spine are set up so that in order to move into extension, we need to first come from a place of relative flexion.

And for rotation, we need to start from a position of relative neutrality. If you don’t believe me, you can feel this on yourself:

View this post on Instagram

Therefore, a thoracic spine stuck in extension will be limited in both extension and rotation.

So can someone explain why we keep doing drills such as those above?

There is nothing wrong with this, so long as we can move out of this position.

Myth #2: The spine is primarily responsible for thoracic spine movement

This one might need a trigger warning.

Your spine doesn’t rotate your spine. Pressure changes rotate your spine.

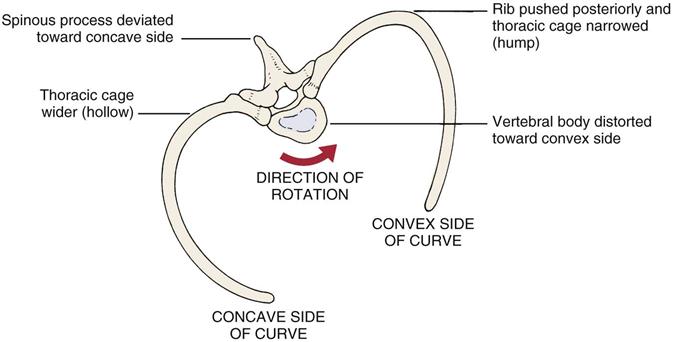

In order for us to turn to (for example) the left (as shown below), we need to be able to have our ribcage adjust shape to allow for that to happen:

This means that the left ribs need to be pushed back and the right ribs need to be pushed forward.

This pressure change in the ribcage is going to create a rotation of the thoracic spine to the left.

Therefore, if our ribcage can’t change pressures, or “expand” and “compress” as it needs to, then we will be lacking in thoracic spine rotation.

The general rule is that we need to be able to externally rotate, or "open up" the ribs on the side we're turning towards and internally rotate, or "close off" the ribs on the side we're turning away from.

You can test your rotation with a simple test such as the seated trunk rotation test:

If you can’t get your shoulder to your belly button without restriction, chances are you are limited in the aforementioned ribcage mechanics that need to happen to allow for that rotation.

Myth #3: Thoracic flexion is bad and dangerous, especially under load

If we understand the concept of a normal human spine curve, then this myth already doesn’t make much sense. However, you may be thinking

“What about kyphosis?”

“Isn’t it bad to lift with a rounded back?”

Kyphosis is usually associated with Upper Crossed Syndrome, where the upper back is excessively rounded:

While we do know that posture is not correlated with pain, we do know that this posture is commonly associated with certain movement restrictions.

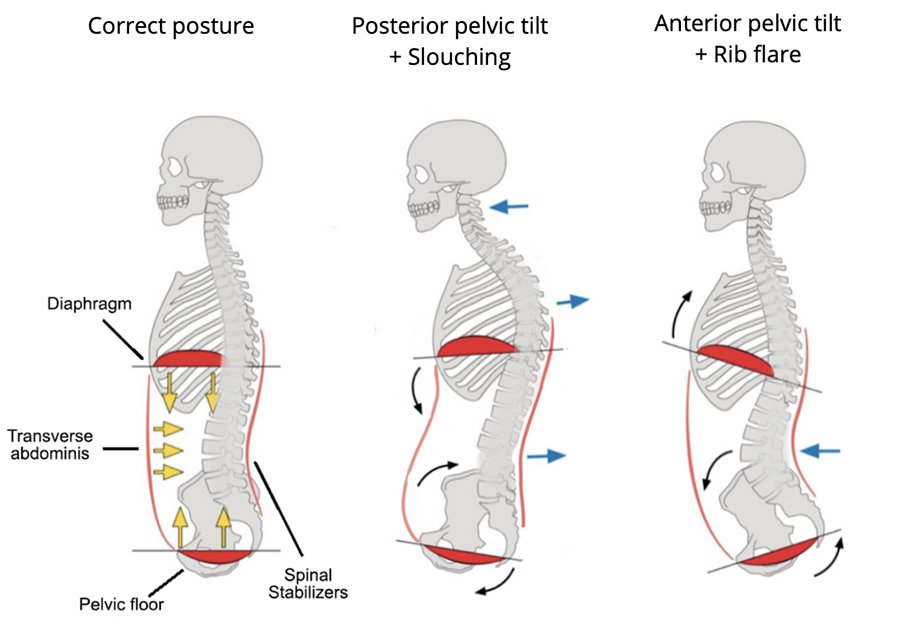

In excessive kyphosis, it is often being driven from a pelvis that is too far forward.

As you can see, the upper back is only going be as rounded as it needs to be to balance out the position of the pelvis. You can learn more about how I address this here.

However, excessive kyphosis is not the same as a healthy degree of thoracic flexion. In fact, thoracic flexion is necessary to create a “Stacked” position of the ribcage over the pelvis:

This position is advantageous to maximize intra-abdominal pressures for lifting weights, but also to create neutrality of the spine to move into other positions.

Here's how I coach it in movements like the squat and deadlift:

How to improve thoracic mobility

Now, what can we do to really address the root of the problem? Here are some strategies:

Exercises to improve thoracic extension & flexion

As mentioned above, the most common problem with limited thoracic extension or flexion is a thoracic spine already too extended or flexed.

In either case, they would benefit from learning how to create that aforementioned stacked position, which is a degree of flexion at the thoracic spine, but here’s the key:

As they flex, they shouldn’t lose any height in their skeleton. If they do, they are just slouching and not actually getting true thoracic flexion.

Here are example exercises to help with this:

How to improve thoracic rotation

If you want to improve thoracic rotation, first make sure you aren’t stuck in extension. If you are, see above.

In the case of improving ribcage internal rotation, we also want to make sure that part of our back can open up.

Here are example loaded variations:

Try these exercises then re-test your seated trunk rotation. If you do them well, you’ll notice a significant change in your ability to rotate, and when you walk you’ll notice how much free your arms and ribs move because you’ve restored that ability to alternate that expansion and compression from side-to-side.

If you're looking for more strategies to improve movement to help your clients feel great, check out my free webinar: 5 Strategies To Help Your Clients Feel 85% Better Immediately

Summary

Improving thoracic mobility is so much more than simply trying to force our spines in to an end-range position.

The thoracic spine responds to the position of the lumbar (and cervical) spine as well as how dynamic your ribcage is.

Appreciating that can help you achieve lasting results in improving rotation because you’ll actually have space to move into.

Don’t miss out on free education

Join our email list to receive exclusive content on how to feel & move better.